|

|

|

|

|

|

|

I have used the word "encapsulation" in this book to refer to the process of wrapping up a sequence of instructions in a function, in order to separate the function's interface (how to use it) from its implementation (how it does what it does).

This kind of encapsulation might be called "functional encapsulation," to distinguish it from "data encapsulation," which is the topic of this chapter. Data encapsulation is based on the idea that each structure definition should provide a set of functions that apply to the structure, and prevent unrestricted access to the internal representation.

One use of data encapsulation is to hide implementation details from users or programmers that don't need to know them.

For example, there are many possible representations for a Card, including two integers, two strings and two enumerated types. The programmer who writes the Card member functions needs to know which implementation to use, but someone using the Card structure should not have to know anything about its internal structure.

As another example, we have been using string and vector objects without ever discussing their implementations. There are many possibilities, but as "clients" of these libraries, we don't need to know.

In C++, the most common way to enforce data encapsulation is to prevent client programs from accessing the instance variables of an object. The keyword private is used to protect parts of a structure definition. For example, we could have written the Card definition:

struct CardThere are two sections of this definition, a private part and a public part. The functions are public, which means that they can be invoked by client programs. The instance variables are private, which means that they can be read and written only by Card member functions.

It is still possible for client programs to read and write the instance variables using the accessor functions (the ones beginning with get and set). On the other hand, it is now easy to control which operations clients can perform on which instance variables. For example, it might be a good idea to make cards "read only" so that after they are constructed, they cannot be changed. To do that, all we have to do is remove the set functions.

Another advantage of using accessor functions is that we can change the internal representations of cards without having to change any client programs.

In most object-oriented programming languages, a class is a user-defined type that includes a set of functions. As we have seen, structures in C++ meet the general definition of a class.

But there is another feature in C++ that also meets this definition; confusingly, it is called a class. In C++, a class is just a structure whose instance variables are private by default. For example, I could have written the Card definition:

class CardI replaced the word struct with the word class and removed the private: label. This result of the two definitions is exactly the same.

In fact, anything that can be written as a struct can also be written as a class, just by adding or removing labels. There is no real reason to choose one over the other, except that as a stylistic choice, most C++ programmers use class.

Also, it is common to refer to all user-defined types in C++ as "classes," regardless of whether they are defined as a struct or a class.

As a running example for the rest of this chapter we will consider a class definition for complex numbers. Complex numbers are useful for many branches of mathematics and engineering, and many computations are performed using complex arithmetic. A complex number is the sum of a real part and an imaginary part, and is usually written in the form x + yi, where x is the real part, y is the imaginary part, and i represents the square root of –1.

The following is a class definition for a user-defined type called Complex:

class ComplexBecause this is a class definition, the instance variables real and imag are private, and we have to include the label public: to allow client code to invoke the constructors.

As usual, there are two constructors: one takes no parameters and does nothing; the other takes two parameters and uses them to initialize the instance variables.

So far there is no real advantage to making the instance variables private. Let's make things a little more complicated; then the point might be clearer.

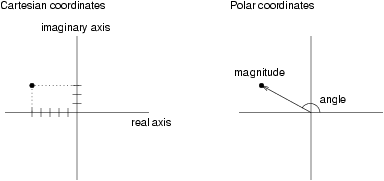

There is another common representation for complex numbers that is sometimes called "polar form" because it is based on polar coordinates. Instead of specifying the real part and the imaginary part of a point in the complex plane, polar coordinates specify the direction (or angle) of the point relative to the origin, and the distance (or magnitude) of the point.

The following figure shows the two coordinate systems graphically.

Complex numbers in polar coordinates are written r ei theta, where r is the magnitude (radius), and theta is the angle in radians.

Fortunately, it is easy to convert from one form to another. To go from Cartesian to polar,

| r = √(x2

+ y2) theta = arctan (y / x) |

To go from polar to Cartesian,

| x = r cos theta y = r sin theta |

So which representation should we use? Well, the whole reason there are multiple representations is that some operations are easier to perform in Cartesian coordinates (like addition), and others are easier in polar coordinates (like multiplication). One option is that we can write a class definition that uses both representations, and that converts between them automatically, as needed.

class ComplexThere are now six instance variables, which means that this representation will take up more space than either of the others, but we will see that it is very versatile.

Four of the instance variables are self-explanatory. They contain the real part, the imaginary part, the angle and the magnitude of the complex number. The other two variables, cartesian and polar are flags that indicate whether the corresponding values are currently valid.

For example, the do-nothing constructor sets both flags to false to indicate that this object does not contain a valid complex number (yet), in either representation.

The second constructor uses the parameters to initialize the real and imaginary parts, but it does not calculate the magnitude or angle. Setting the polar flag to false warns other functions not to access mag or theta until they have been set.

Now it should be clearer why we need to keep the instance variables private. If client programs were allowed unrestricted access, it would be easy for them to make errors by reading uninitialized values. In the next few sections, we will develop accessor functions that will make those kinds of mistakes impossible.

By convention, accessor functions have names that begin with get and end with the name of the instance variable they fetch. The return type, naturally, is the type of the corresponding instance variable.

In this case, the accessor functions give us an opportunity to make sure that the value of the variable is valid before we return it. Here's what getReal looks like:

double Complex::getReal ()If the cartesian flag is true then real contains valid data, and we can just return it. Otherwise, we have to call calculateCartesian to convert from polar coordinates to Cartesian coordinates:

void Complex::calculateCartesian ()Assuming that the polar coordinates are valid, we can calculate the Cartesian coordinates using the formulas from the previous section. Then we set the cartesian flag, indicating that real and imag now contain valid data.

As an exercise, write a corresponding function called calculatePolar and then write getMag and getTheta. One unusual thing about these accessor functions is that they are not const, because invoking them might modify the instance variables.

As usual when we define a new class, we want to be able to output objects in a human-readable form. For Complex objects, we could use two functions:

void Complex::printCartesian ()The nice thing here is that we can output any Complex object in either format without having to worry about the representation. Since the output functions use the accessor functions, the program will compute automatically any values that are needed.

The following code creates a Complex object using the second constructor. Initially, it is in Cartesian format only. When we invoke printCartesian it accesses real and imag without having to do any conversions.

Complex c1 (2.0, 3.0);When we invoke printPolar, and printPolar invokes getMag, the program is forced to convert to polar coordinates and store the results in the instance variables. The good news is that we only have to do the conversion once. When printPolar invokes getTheta, it will see that the polar coordinates are valid and return theta immediately.

The output of this code is:

2 + 3iA natural operation we might want to perform on complex numbers is addition. If the numbers are in Cartesian coordinates, addition is easy: you just add the real parts together and the imaginary parts together. If the numbers are in polar coordinates, it is easiest to convert them to Cartesian coordinates and then add them.

Again, it is easy to deal with these cases if we use the accessor functions:

Complex add (Complex& a, Complex& b)Notice that the arguments to add are not const because they might be modified when we invoke the accessors. To invoke this function, we would pass both operands as arguments:

Complex c1 (2.0, 3.0);The output of this program is

5 + 7iAnother operation we might want is multiplication. Unlike addition, multiplication is easy if the numbers are in polar coordinates and hard if they are in Cartesian coordinates (well, a little harder, anyway).

In polar coordinates, we can just multiply the magnitudes and add the angles. As usual, we can use the accessor functions without worrying about the representation of the objects.

Complex mult (Complex& a, Complex& b)A small problem we encounter here is that we have no constructor that accepts polar coordinates. It would be nice to write one, but remember that we can only overload a function (even a constructor) if the different versions take different parameters. In this case, we would like a second constructor that also takes two doubles, and we can't have that.

An alternative it to provide an accessor function that sets the instance variables. In order to do that properly, though, we have to make sure that when mag and theta are set, we also set the polar flag. At the same time, we have to make sure that the cartesian flag is unset. That's because if we change the polar coordinates, the cartesian coordinates are no longer valid.

void Complex::setPolar (double m, double t)As an exercise, write the corresponding function named setCartesian.

To test the mult function, we can try something like:

Complex c1 (2.0, 3.0);The output of this program is

-6 + 17iThere is a lot of conversion going on in this program behind the scenes. When we call mult, both arguments get converted to polar coordinates. The result is also in polar format, so when we invoke printCartesian it has to get converted back. Really, it's amazing that we get the right answer!

There are several conditions we expect to be true for a proper Complex object. For example, if the cartesian flag is set then we expect real and imag to contain valid data. Similarly, if polar is set, we expect mag and theta to be valid. Finally, if both flags are set then we expect the other four variables to be consistent; that is, they should be specifying the same point in two different formats.

These kinds of conditions are called invariants, for the obvious reason that they do not vary—they are always supposed to be true. One of the ways to write good quality code that contains few bugs is to figure out what invariants are appropriate for your classes, and write code that makes it impossible to violate them.

One of the primary things that data encapsulation is good for is helping to enforce invariants. The first step is to prevent unrestricted access to the instance variables by making them private. Then the only way to modify the object is through accessor functions and modifiers. If we examine all the accessors and modifiers, and we can show that every one of them maintains the invariants, then we can prove that it is impossible for an invariant to be violated.

Looking at the Complex class, we can list the functions that make assignments to one or more instance variables:

the second constructorIn each case, it is straightforward to show that the function maintains each of the invariants I listed. We have to be a little careful, though. Notice that I said "maintain" the invariant. What that means is "If the invariant is true when the function is called, it will still be true when the function is complete."

That definition allows two loopholes. First, there may be some point in the middle of the function when the invariant is not true. That's ok, and in some cases unavoidable. As long as the invariant is restored by the end of the function, all is well.

The other loophole is that we only have to maintain the invariant if it was true at the beginning of the function. Otherwise, all bets are off. If the invariant was violated somewhere else in the program, usually the best we can do is detect the error, output an error message, and exit.

Often when you write a function you make implicit assumptions about the parameters you receive. If those assumptions turn out to be true, then everything is fine; if not, your program might crash.

To make your programs more robust, it is a good idea to think about your assumptions explicitly, document them as part of the program, and maybe write code that checks them.

For example, let's take another look at calculateCartesian. Is there an assumption we make about the current object? Yes, we assume that the polar flag is set and that mag and theta contain valid data. If that is not true, then this function will produce meaningless results.

One option is to add a comment to the function that warns programmers about the precondition.

void Complex::calculateCartesian ()At the same time, I also commented on the postconditions, the things we know will be true when the function completes.

These comments are useful for people reading your programs, but it is an even better idea to add code that checks the preconditions, so that we can print an appropriate error message:

void Complex::calculateCartesian ()The exit function causes the program to quit immediately. The return value is an error code that tells the system (or whoever executed the program) that something went wrong.

This kind of error-checking is so common that C++ provides a built-in function to check preconditions and print error messages. If you include the assert.h header file, you get a function called assert that takes a boolean value (or a conditional expression) as an argument. As long as the argument is true, assert does nothing. If the argument is false, assert prints an error message and quits. Here's how to use it:

void Complex::calculateCartesian ()The first assert statement checks the precondition (actually just part of it); the second assert statement checks the postcondition.

In my development environment, I get the following message when I violate an assertion:

Complex.cpp:63: void Complex::calculatePolar(): Assertion `cartesian' failed.There is a lot of information here to help me track down the error, including the file name and line number of the assertion that failed, the function name and the contents of the assert statement.

In some cases, there are member functions that are used internally by a class, but that should not be invoked by client programs. For example, calculatePolar and calculateCartesian are used by the accessor functions, but there is probably no reason clients should call them directly (although it would not do any harm). If we wanted to protect these functions, we could declare them private the same way we do with instance variables. In that case the complete class definition for Complex would look like:

class ComplexThe private label at the beginning is not necessary, but it is a useful reminder.

Revised 2009-04-13.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|