|

|

|

|

|

|

|

This chapter presents a new data structure called a tree, some of its uses and two ways to implement it.

A possible source of confusion is the distinction between an ADT, a data structure, and an implementation of an ADT or data structure. There is no universal answer, because something that is an ADT at one level might in turn be the implementation of another ADT.

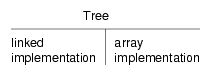

To help keep some of this straight, it is sometimes useful to draw a diagram showing the relationship between an ADT and its possible implementations. This figure shows that there are two implementations of a tree:

The horizontal line in the figure represents the barrier of abstraction between the ADT and its implementations.

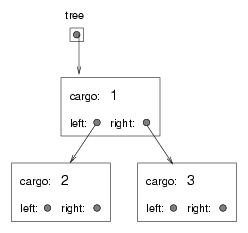

Like lists, trees are made up of nodes. A common kind of tree is a binary tree, in which each node contains a reference to two other nodes (possibly null). The class definition looks like this:

class Tree {Like list nodes, tree nodes contain cargo: in this case an int. However, trees may consist of any type of cargo, so in the future you could prefix the definition with template <class ITEMTYPE> and substitute ITEMTYPE for int and it should work, that is, if the rest of your program code does not go awry. The other instance variables are named left and right, in accordance with a standard way to represent trees graphically:

The top of the tree (the node referred to by tree) is called the root. In keeping with the tree metaphor, the other nodes are called branches and the nodes at the tips with null references are called leaves. It may seem odd that we draw the picture with the root at the top and the leaves at the bottom, but that is not the strangest thing.

To make things worse, computer scientists mix in yet another metaphor: the family tree. The top node is sometimes called a parent and the nodes it refers to are its children. Nodes with the same parent are called siblings, and so on.

Finally, there is also a geometric vocabulary for taking about trees. I already mentioned left and right, but there is also "up" (toward the parent/root) and down (toward the children/leaves). Also, all the nodes that are the same distance from the root comprise a level of the tree.

I don't know why we need three metaphors for talking about trees, but there it is.

The process of assembling tree nodes is similar to the process of assembling lists. We have a constructor for tree nodes that initializes the instance variables.

public:We allocate the child nodes first:

Tree* left = new Tree (2, NULL, NULL);We can create the parent node and link it to the children at the same time:

Tree* tree = new Tree (1, left, right);This code produces the state shown in the previous figure.

By now, any time you see a new data structure, your first question should be, "How can I traverse it?" The most natural way to traverse a tree is recursively. For example, to add up all the integers in a tree, we could write this class method:

int total (Tree* tree) {This is a nonmember function because we would like to use NULL to represent the empty tree, and make the empty tree the base case of the recursion. If the tree is empty, the method returns 0. Otherwise it makes two recursive calls to find the total value of its two children. Finally, it adds in its own cargo and returns the total.

Although this method works, there is some difficulty fitting it into an object-oriented design. It should not appear in the Tree class because it requires the cargo to be int objects. If we make that assumption then we lose the advantages of a generic data structure.

On the other hand, this code accesses the instance variables of the Tree nodes, so it "knows" more than it should about the implementation of the tree. If we changed that implementation later (and we will) this code would break.

Later in this chapter we will develop ways to solve this problem, allowing client code to traverse trees containing any kinds of objects without breaking the abstraction barrier between the client code and the implementation. Before we get there, let's look at an application of trees.

A tree is a natural way to represent the structure of an expression. Unlike other notations, it can represent the computation unambiguously. For example, the infix expression 1 + 2 * 3 is ambiguous unless we know that the multiplication happens before the addition.

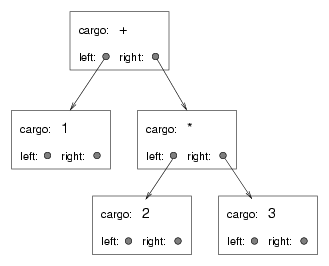

The following figure represents the same computation:

The nodes can be operands like 1 and 2 or operators like + and * (and so the type of the cargo might be string). Operands are leaf nodes; operator nodes contain references to their operands (all of these operators are binary, meaning they have exactly two operands).

Looking at this figure, there is no question what the order of operations is: the multiplication happens first in order to compute the first operand of the addition.

Expression trees like this have many uses. The example we are going to look at is translation from one format (postfix) to another (infix). Similar trees are used inside compilers to parse, optimize and translate programs.

I already pointed out that recursion provides a natural way to traverse a tree. We can print the contents of an expression tree like this:

void print (Tree* tree) {In other words, to print a tree, first print the contents of the root, then print the entire left subtree, then print the entire right subtree. This way of traversing a tree is called a preorder, because the contents of the root appear before the contents of the children.

For the example expression the output is + 1 * 2 3. This is different from both postfix and infix; it is a new notation called prefix, in which the operators appear before their operands.

You might suspect that if we traverse the tree in a different order we get the expression in a different notation. For example, if we print the subtrees first, and then the root node:

void printPostorder (Tree* tree) {We get the expression in postfix (1 2 3 * +)! As the name of the previous method implies, this order of traversal is called postorder. Finally, to traverse a tree inorder, we print the left tree, then the root, then the right tree:

void printInorder (Tree* tree) {The result is 1 + 2 * 3, which is the expression in infix.

To be fair, I have to point out that I have omitted an important complication. Sometimes when we write an expression in infix we have to use parentheses to preserve the order of operations. So an inorder traversal is not quite sufficient to generate an infix expression.

Nevertheless, with a few improvements, the expression tree and the three recursive traversals provide a general way to translate expressions from one format to another.

As I mentioned before, there is a problem with the way we have been traversing trees: it breaks down the barrier between the client code (the application that uses the tree) and the provider code (the Tree implementation). Ideally, tree code should be general; it shouldn't know anything about expression trees. And the code that generates and traverses the expression tree shouldn't know about the implementation of the trees. This design criterion is called object encapsulation to distinguish it from the encapsulation we saw in Section 6.6, which we might call function encapsulation.

In the current version, the Tree code knows too much about the client. Instead, the Tree class should provide the general capability of traversing a tree in various ways. As it traverses, it should perform operations on each node that are specified by the client.

To facilitate this separation of interests, we will create a new abstract class, called Visitable. The items stored in a tree will be required to be visitable, which means that they define a method named visit that does whatever the client wants done to each node. That way the Tree can perform the traversal and the client can perform the node operations.

Here are the steps we have to perform to wedge an abstract class between a client and a provider:

The next few sections demonstrate these steps.

An abstract class definition looks a lot like an ordinary definition, except that it only specifies the interface of each function and not an implementation. The definition of Visitable is

class Visitable {That's it! An abstract class is a class that contains at least one pure virtual function, such as visit, whereas a concrete class provides an implementation for every function. The definition of visit looks like any other function definition, except that its body is the pure specifier = 0. This definition specifies that any class that implements Visitable has to have a function named visit that takes no parameters and that returns void.

If we are using an expression tree to generate infix, then "visiting" a node means printing its contents. Since the contents of an expression tree are tokens, we'll create a new concrete class called Token that is derived from Visitable:

class Token : public Visitable {When we compile this class definition, the compiler checks whether the functions provided satisfy the requirements specified by the abstract class. For example, if we misspell the name of the function that is supposed to be visit, the resulting class Token would still be abstract (since it doesn't define visit).

The next step is to modify the parser to put Token objects into the tree instead of strings. Here is a small example:

string expr = "1 2 3 * +";This code takes the first token in the string and wraps it in a Token object, then puts the Token into a tree node. If the Tree requires the cargo to be Visitable, it will convert the Token to be a Visitable object. When we remove the Visitable from the tree, we will have to cast it back into a Token.

As an exercise, write a version of printPreorder called visitPreorder that traverses the tree and invokes visit on each node in preorder.

What does it mean to "implement" a tree? So far we have only seen one implementation of a tree, a linked data structure similar to a linked list. But there are other structures we would like to identify as trees. Anything that can perform the basic set of tree operations should be recognized as a tree.

So what are the tree operations? In other words, how do we define the Tree ADT?

In the implementation we have seen, the empty tree is represented by the special value NULL. left and right are performed by accessing the instance variables of the node. We have not implemented parent yet (you might think about how to do it).

There is another implementation of trees that uses arrays and indices instead of objects and references. To see how it works, we will start by looking at a hybrid implementation that uses both arrays and objects.

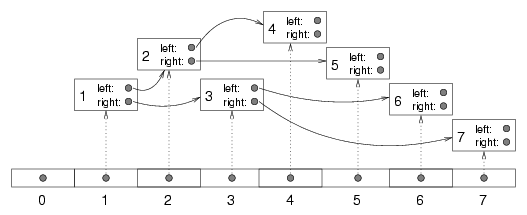

This figure shows a tree like the ones we have been looking at, although it is laid out sideways, with the root at the left and the leaves on the right. At the bottom there is an array of references that refer to the objects in the trees.

In this tree the cargo of each node is the same as the array index of the node, but of course that is not true in general. You might notice that array index 1 refers to the root node and array index 0 is empty. The reason for that will become clear soon.

So now we have a tree where each node has a unique index. Furthermore, the indices have been assigned to the nodes according to a deliberate pattern, in order to achieve the following results:

Using these formulas, we can implement left, right and parent just by doing arithmetic; we don't have to use the references at all!

Since we don't use the references, we can get rid of them, which means that what used to be a tree node is now just cargo and nothing else. That means we can implement the tree as an array of cargo objects; we don't need tree nodes at all.

Here's what one implementation looks like:

template <class Object>No surprises so far. The instance variable is an array of Objects. The constructor initializes this array with an arbitrary initial size (we can always resize it later).

To check whether a tree is empty, we check whether the root node is null. Again, the root node is located at index 1.

bool empty () {The implementation of left, right and parent is just arithmetic:

int left (int i) { return 2*i; }Only one problem remanins. The node "references" we have are not really references; they are integer indices. To access the cargo itself, we have to get or set an element of the array. For that kind of operation, it is often a good idea to provide methods that perform simple error checking before accessing the data structure.

Object* getCargo (int i) {Methods like this are often called accessor methods because they provide access to a data structure (the ability to get and set elements) without letting the client see the details of the implementation.

Finally we are ready to build a tree. In another class (the client), we would write:

Tree<string> tree = new Tree<string> ();The constructor builds an empty tree. In this case we assume that the client knows that the index of the root is 1 although it would be preferable for the tree implementation to provide that information. Anyway, invoking setCargo puts the string "cargo for root" into the root node.

To add children to the root node:

tree.setCargo (tree.left (root), new "cargo for left");In the tree class we could provide a method that prints the contents of the tree in preorder.

void printPreorder (int i) {We invoke this method from the client by passing the root as a parameter.

tree.print (root);The output is

cargo for rootThis implementation provides the basic operations required to be a tree, but it leaves a lot to be desired. As I pointed out, we expect the client to have a lot of information about the implementation, and the interface the client sees, with indices and all, is not very pretty.

Also, we have the usual problem with array implementations, which is that the initial size of the array is arbitrary and it might have to be resized.

As you've seen, vector<T> is a Standard C++ class provided in the vector package. It is an implementation of an array of items of a specified type T, with the added feature that it can resize itself automatically, so we don't have to.

The vector class provides a function named at() that is similar to the square brackets [], but signals an error if you attempt to subscript outside of the vectors bounds. Thus v.at(i) can be used as either an lvalue or an rvalue, just like v[i]. You should review the other vector operations by consulting the online documentation for the C++ Standard Template Library (STL) for vector containers.

Before using the vector class, you should understand a few concepts. Every vector has a capacity, which is the amount of space that has been allocated to store values, and a size, which is the number of values that are actually in the vector.

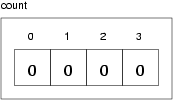

The following figure is a simple diagram of a vector<int> that contains three elements, but it has a capacity of seven.

In general, it is the responsibility of the client code to make sure that the vector has sufficient size before invoking at. If you try to access an element that does not exist (in this case the elements with indices 4 through 6), you will get an out_of_range exception.

The vector member functions include push_back and insert, which automatically increase the size of the vector, but at does not. The resize method adds elements to the end of the vector to get to the given size; they are initialized by the default constructor for the item type, T().

Most of the time the client doesn't have to worry about capacity. Whenever the size of the vector changes, the capacity is automatically updated, if necessary. For performance reasons, some applications might want to take control of this function, which is why there are additional member functions for increasing and decreasing capacity.

Because the client code has no access to the implementation of a vector, it is not clear how we should traverse one. Of course, one possibility is to use a loop variable as an index into the vector:

for (int i=0; i<v.size(); i++) {There's nothing wrong with that, but there is another way that serves to demonstrate the iterator class. Vectors provide a member functions named begin() and end() that return iterator objects that makes it possible to traverse the vector.

The iterator type is defined for the vector library. It specifies three member functions (among others) for vectors:

The following example uses an iterator to traverse and print the elements of a vector vec.

vector<int>::iterator it;Once the iterator is created, it is a separate object from the original vector. Subsequent changes in the vector are not reflected in the iterator. In fact, if you modify the vector after creating an iterator, the iterator becomes invalid. If you access the iterator again, it will cause an error.

In a previous section we used the Visitable abstract class to allow a client to traverse a data structure without knowing the details of its implementation. Iterators provide another way to do the same thing. In the first case, the provider performs the iteration and invokes client code to "visit" each element. In the second case the provider gives the client an object that it can use to select elements one at a time (albeit in an order controlled by the provider).

As an exercise, write a concrete class named preIterator that implements the iterator interface, and write a function named preorderIterator for the Tree class that returns a PreIterator that selects the elements of the Tree in preorder.

Revised 2008-12-12.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|